During my last co-op, I was tasked with migrating some services to CircleCI. Due to some complications with local development, my testing process consisted of committing my changes, pushing to a remote branch, and seeing if the build passed. Unfortunately, this led to lots of ugly, super minor commits, often with fairly careless commit messages.

After I squashed all of the bugs, I was left with a bunch of uninformative commits with seemingly meaningless messages like “trying this” and “it should work now” (it didn’t work). Fortunately, one of my coworkers introduced me to interactive rebasing.

When I first learned about git, git commit --amend was a staple in my workflow. There was a lot of pressure to write concise, yet descriptive commit messages, especially when I was pairing with a coworker. The command loads the previous commit message into your editor and allows you to change the message. This is great, but it only works for renaming the most recent commit.

Interactive rebasing is like the super hero version of git commit --amend. Rebasing can solve some of the same problems as merging can, but for this guide, I’ll just be talking about using it in interactive mode to rewrite your history.

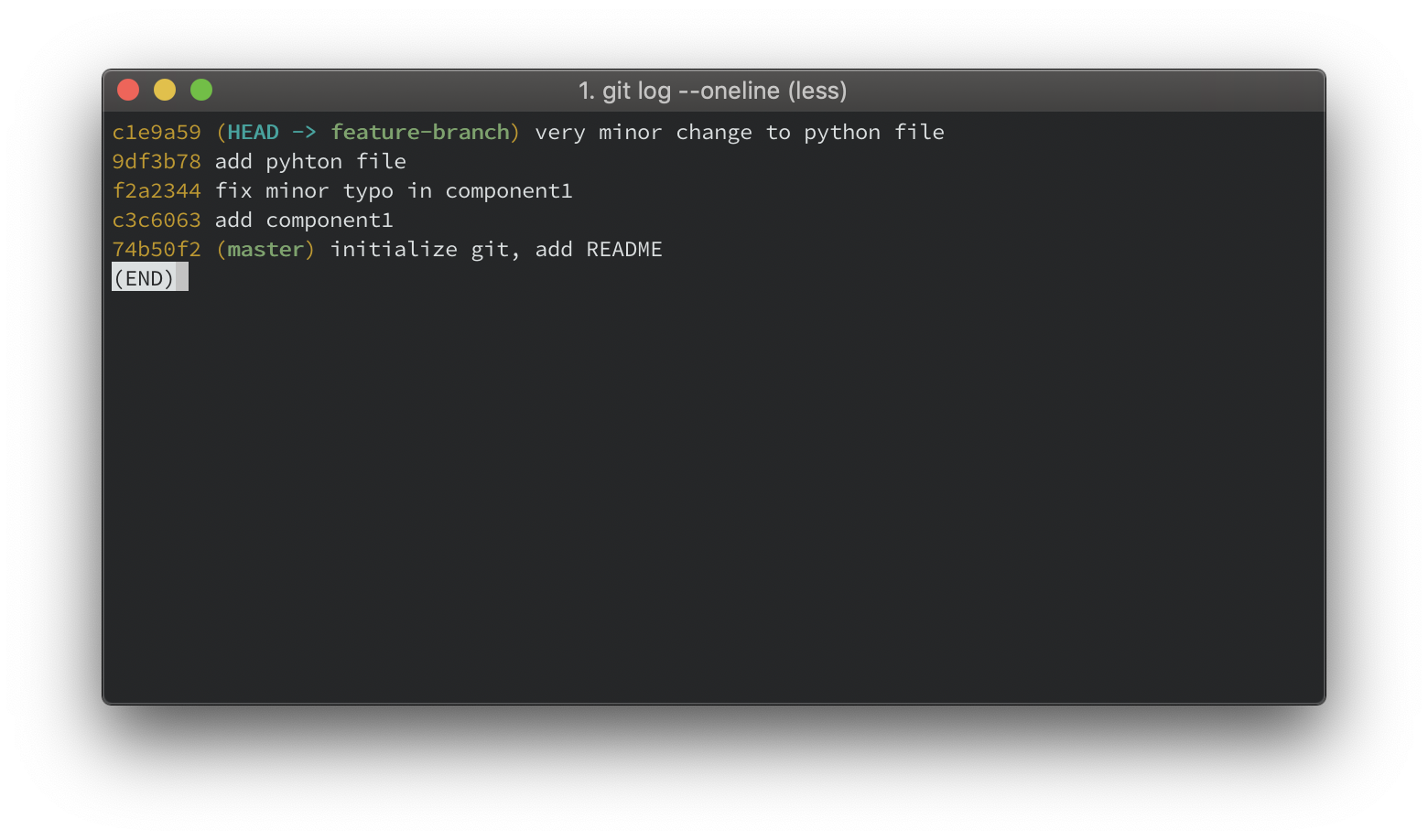

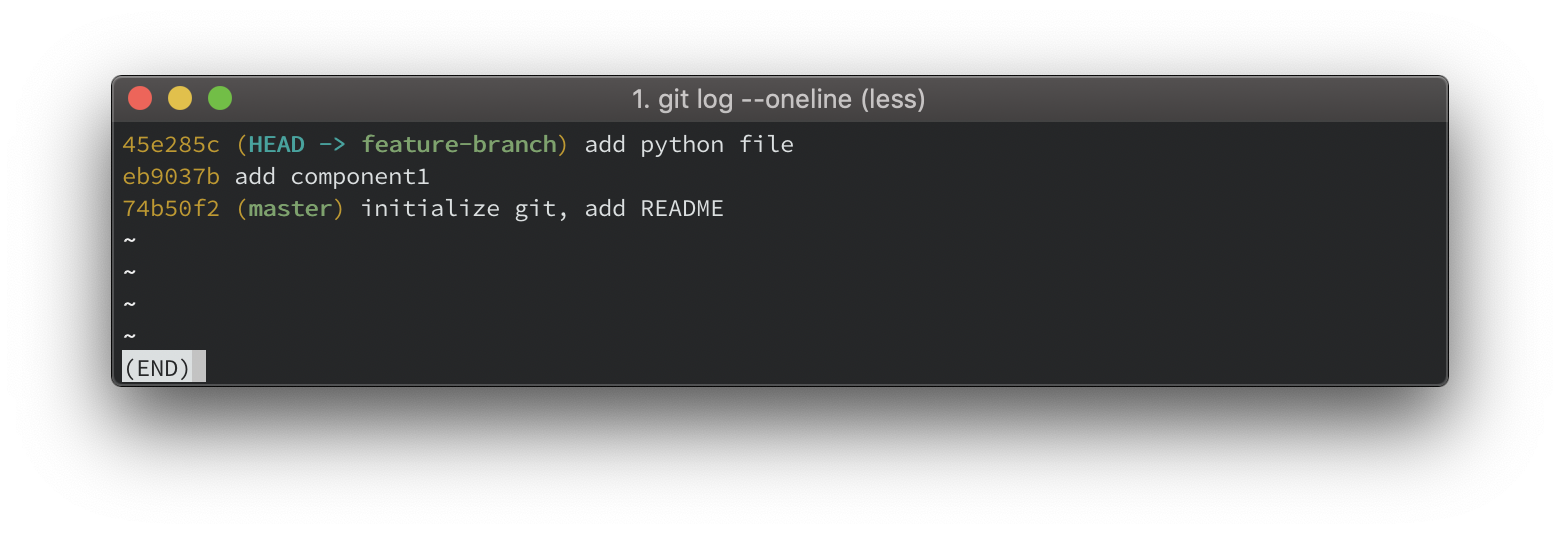

Let’s start with an example:

The commits in the previous photo are show newest (top) to oldest (bottom). So we have our master branch, and we’ve checked out to a new branch called feature-branch. In this new branch we’ve made 4 commits:

- Add a major component

- Fix a typo in the component. This doesn’t need its own commit and we wish it was part of the previous commit.

- Add a new python file, but we have a typo in the commit message.

- Make a minor change to the python file. Let’s say this change is minor enough that it probably doesn’t deserve its own commit.

Important Warning

Interactive rebasing shouldn’t be used on public branches. It rewrites the history, which can be destructive if other people are working on the same branch. These operations are irreversible. If you really want to rebase your public branches, check with your team and make sure they’re all okay with it.

If you’ve already pushed commits to a remote repo (probably in a PR), you’ll need to do the interactive rebase locally, then force push your feature branch. I suggest using git push --force-with-lease to ensure you’re not clobbering other people’s changes with your force push.

Interactive Rebase

Let’s clean up our commits. First, we need to decide how far back we want to rewrite our commits. We can pick a specific SHA, reference based on where our HEAD pointer is (HEAD-5 will let us edit the last 5 commits), or we can edit all the commits from this branch (master). Let’s do the last option. From our feature branch, we’ll run:

git rebase -i master

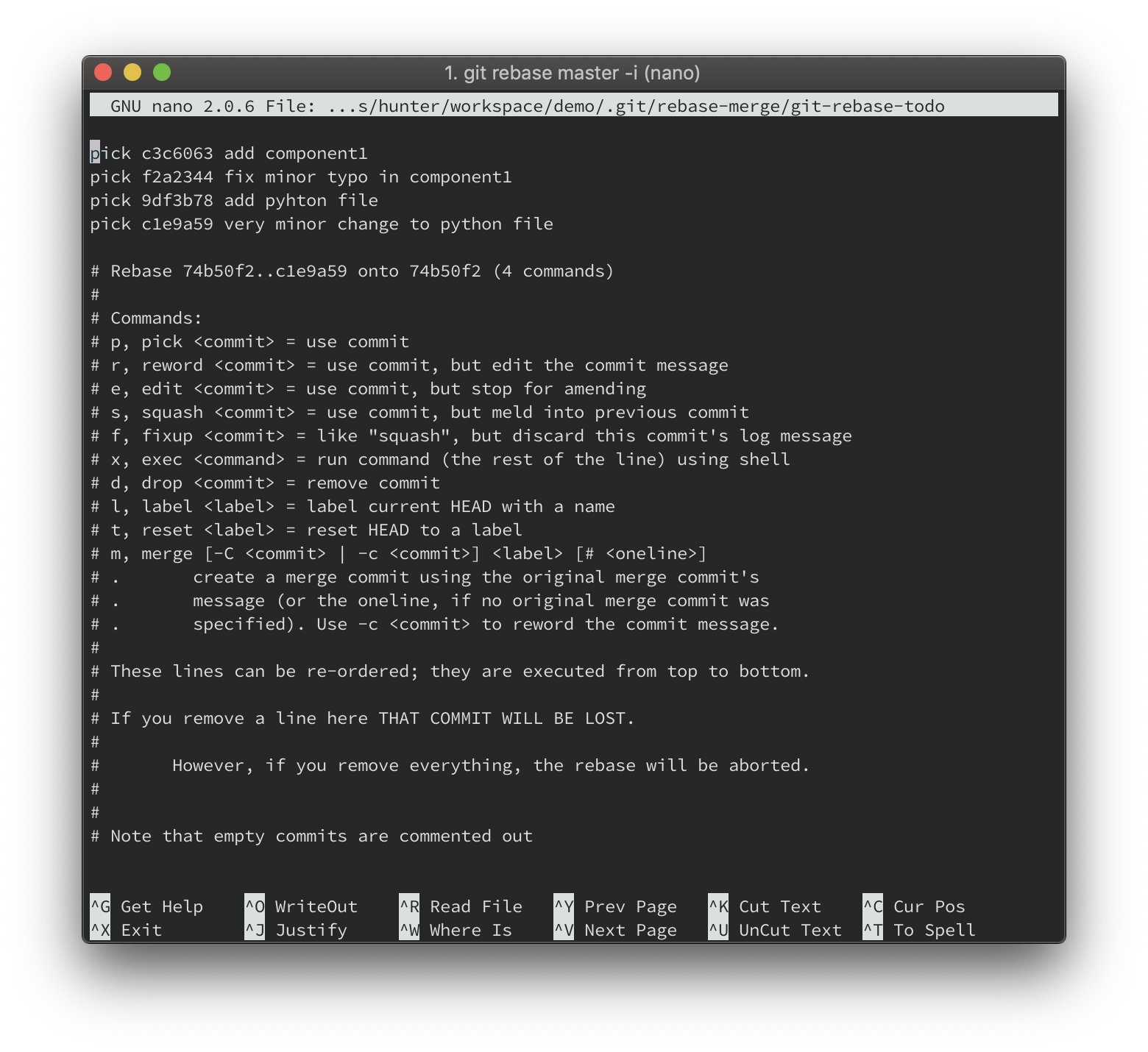

When we run the command, something like this will pop up in a text editor. It’s a little overwhelming, but if we break it up into components it makes a lot of sense.

The first section shows the commits we are editing in the following format: <command> <SHA> <commit message>. The next important section is the set of commands. For this post, we’ll only be looking at pick, reword, and fixup. If you want to read more about the other options, there’s lot of documentation online.

- pick is the default. This will use the commit without altering it at all.

- reword lets us edit the commit message. This is slightly different than edit, which lets us change other aspects of the commit.

- fixup merges the commit to the previous commit. This is useful when adding a very minor change onto a different commit.

We can also use the shortened version of the commands - p, r, and f respectively.

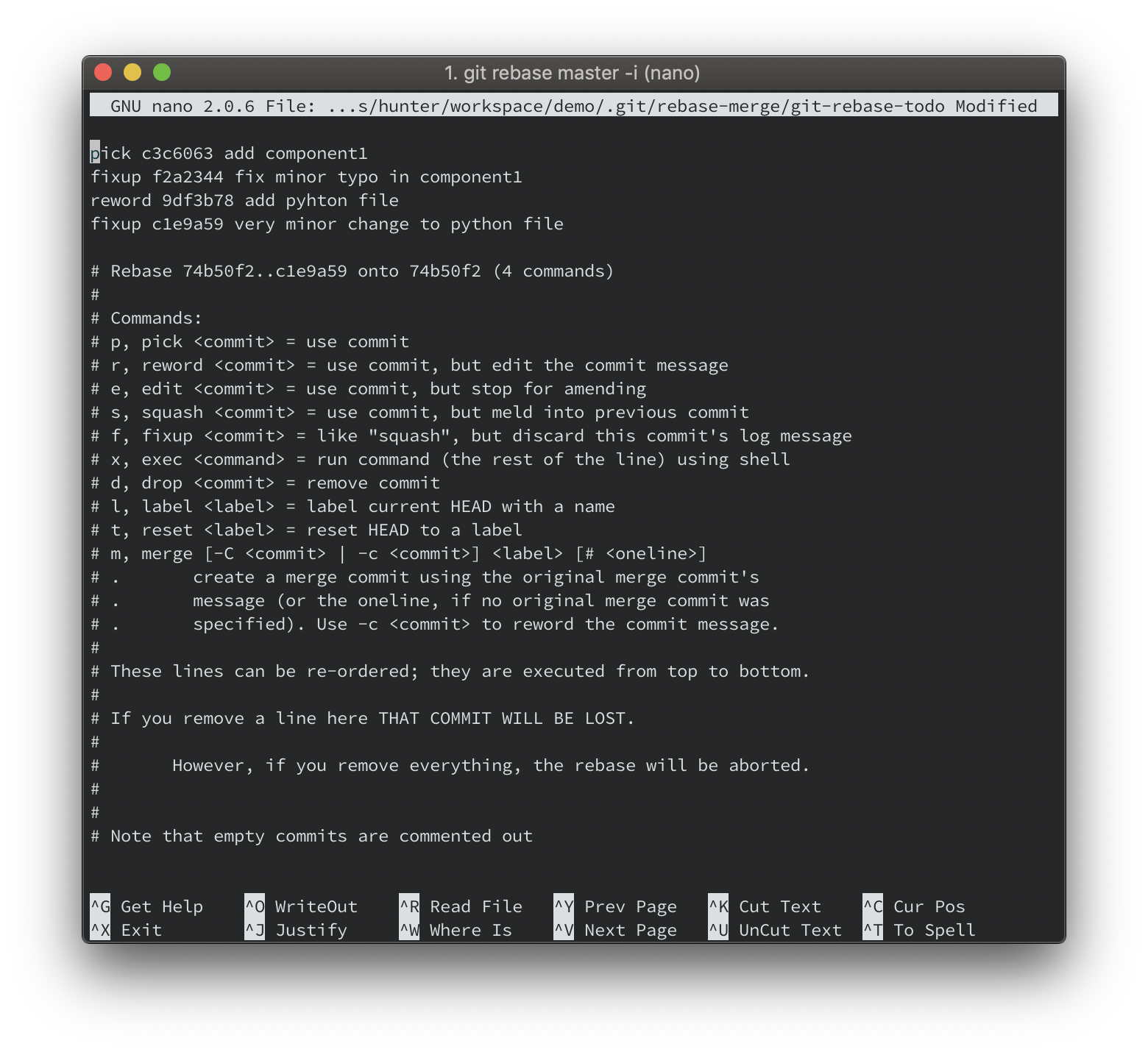

Now that we know how to use these commands, let’s make some changes to our history. We want to keep our first commit how it is (pick), combine our second commit with our first (fixup), reword our third commit message (reword), and combine our fourth commit with our third (fixup).

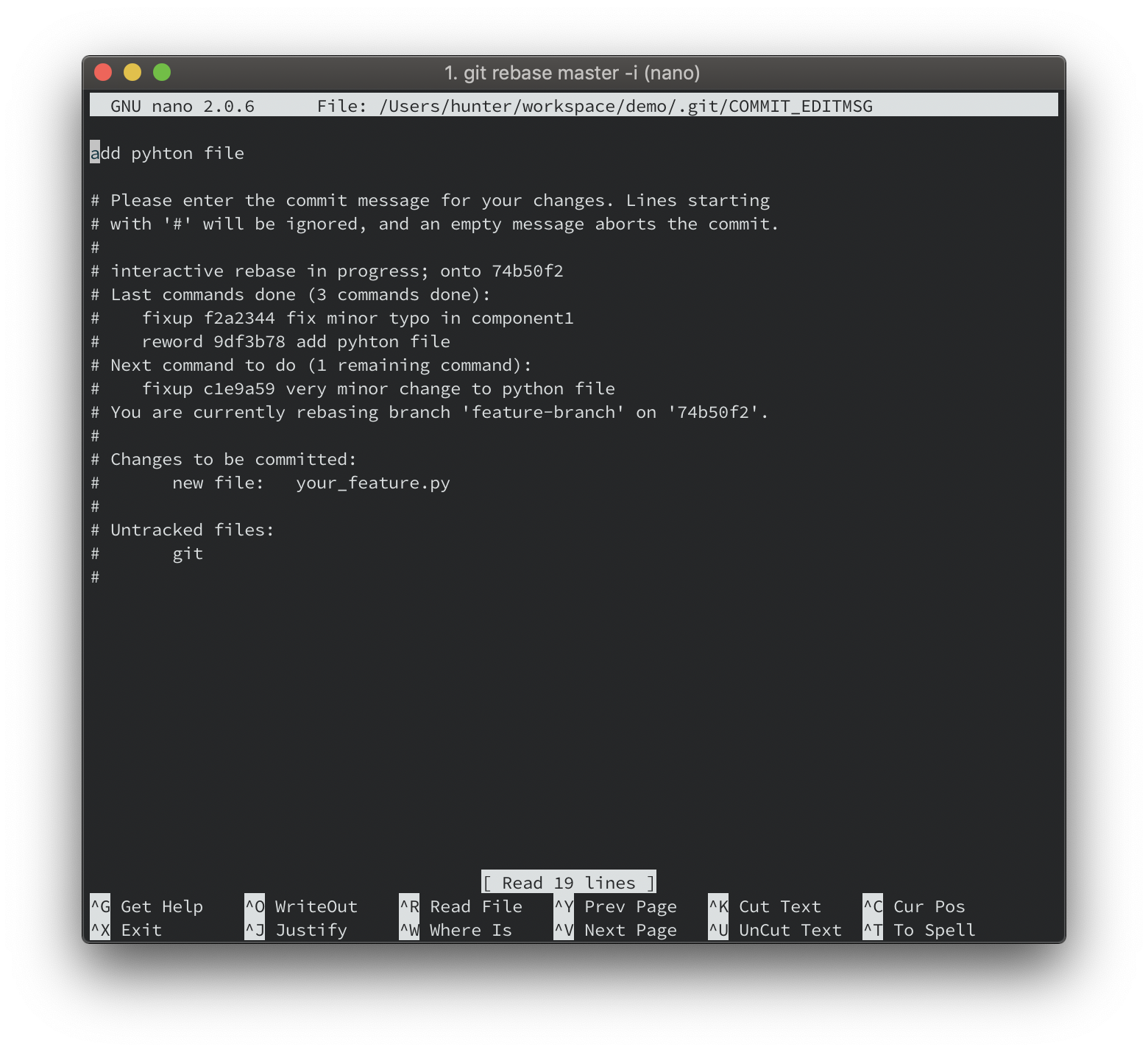

When we save this file, git will work from newest (bottom) to oldest (top), stopping whenever it requires user input. It starts with the fixup operation, which will combine the commit with the previous. Then it will go to the reword operation. The rebase operation will pause and prompt the user to reword the commit.

In the text editor, we can fix the typo in our commit message, save, and exit. This will resume the rebase operation. The next two steps, fixup and pick, don’t require user input, so it will finish and return us to our normal command line prompt. Let’s see what our git logs look like now.

Nice. Our four commits are now two, clean commits without any typos or minor changes. This was a fairly simple example, but interactive rebasing can be super useful for more complex fixes (but make sure you double check everything). It's good practice to clean up your commits before getting a code review, since a clear commit history can communicate your changes and your approach.